MacFarlane, Charles (1828)

1828, fin août

Connu essentiellement par ses œuvres historiques, ses biographies de personnages célèbres (Wellington, Napoléon) et ses récits de voyage, l’écrivain écossais Charles MacFarlane naît en 1799. De 1816 à 1827 il vie en Italie, puis, en 1828-1829, il effectue un séjour de seize mois à Constantinople et dans les provinces turques. En 1829 il s’installe à Londres. En 1847, il repart en Turquie et, sur le chemin du retour, il visite encore une fois l’Italie. Il meurt en 1859 à Londres.

Texte français : Jean-Pierre Grélois

C’est par un jour magnifique, à la fin du mois d’août, que je partis de Galata pour l’île de Prigkipos, la plus grande et peut-être la plus pittoresque et romantique de cet archipel enchanteur appelé îles des Princes. Je pris passage à bord d’un grand caïque, l’un des quelques bateaux qui font quotidiennement la traversée entre Constantinople et les îles. […]

Nous glissions doucement devant les maisons peintes en rouge de Kadıköy, qui occupe pittoresquement, mais humblement, le site de l’ancienne Chalcédoine tant renommée pour ses conciles ; nous doublâmes la langue de terre basse qui se déploie au-delà, dont la pointe extrême est nommée Fenerbahçe […].

Après avoir navigué près de trois heures, nous étions proches de Prôtè, l’une des îles de l’archipel, une petite île riante, verdoyante du sommet jusqu’au bord de l’eau, sans aucune habitation qu’un petit monastère grec. De Prôté un très court trajet nous amena à Chalkè, une île plus grande, plus belle et bien habitée où je débarquai pour prendre un café et fumer une pipe dont le plaisir fut très accru par la vue d’un groupe de jeunes Grecs qui dansaient dans un jardin du bord de l’eau. Je traversai de Chalkè à Prigkipos en moins d’un quart d’heure […].

[…] Un monastère grec sur une colline […] était appelé Christos. Il y avait deux autres monastères sur l’île, l’un appelé Saint-Georges, l’autre Saint-Nicolas. Saint-Georges était situé au sommet d’une hauteur au sud de l’île, qui pourrait mériter l’appellation de montagne. Le chemin qui y mène depuis Christos était, indépendamment des panoramas qu’il offrait, romantique et pittoresque. En laissant le monastère au milieu de bouquets de pins, j’avais l’habitude de suivre une bonne descente dans un vallon qui sépare les lignes de crête de l’île. Dans ce vallon rocailleux, il y avait quelques oliviers, mais il était principalement couvert de broussailles, de thym, de lavande et autres plantes à parfum parmi lesquelles on voyait paître des troupeaux de belles grandes chèvres. De ce vallon un sentier alpestre, escarpé et inégal, montait à flanc de montagne, avec çà et là une croix et un siège de pierre pour prier ou se reposer. Le sentier se terminait par un replat de dimensions limitées, sur lequel se dressait un bosquet d’arbres ondoyants et un ensemble de bâtiments à l’aspect bizarre, mal assorti, le monastère et l’église. Les murs du bâtiment regardant vers l’île de Marmara [..] se dressaient en quelques endroits au bord du précipice, alignés sur les hautes falaises qui étaient presque verticales. […] L’église était petite et misérable. L’intérieur du monastère était principalement en bois et il était occupé, non pas par un essaim de gras moines bourdonnants, mais par un nombre de malheureux Grecs qui avaient perdu l’esprit, soignés seulement par un supérieur et trois ou quatre caloyers. C’était pour tout dire un asile de fous, financé par les donations de Grecs comme les hôpitaux qu’ils ont à Constantinople, à Smyrne et dans la plupart des endroits où il en réside un certain nombre, sous l’administration ou la direction du patriarche ou de quelque prélat.

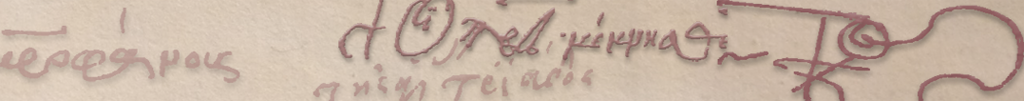

Texte anglais : Ch. Mac Farlane, Constantinople in 1828. A residence of sixteen months in the Turkish capital and provinces: with an account of the present state of the naval and military power, and of the resources of the Ottoman empire, London, 1829, p. 489-491, 499-500 (seconde édition : London, 1829, vol. 2, p. 469 sq.)

[…] It was on a beautiful day, at the end of the month of August, that I took my departure from Galata for the island of Prinkipo, the largest, and perhaps, the most picturesque and romantic of that fairy group, called the Princes’ Islands. I took my passage on board a large caik, one of several passage-boats that run daily between Constantinople and the islands. […]

We glided gently past the red painted wooden houses at Cadikeui, the picturesque but humble occupant of the site of the ancient Chalcedonia, so famed for its ecclesiastical councils ; we doubled the low gentle slip of land that extends beyond it, the extreme point of which is denominated Fanar Backshi […].

After slowly sailing for nearly two hours, we were close into Proté, one of the group — a smiling little island, green from its summit to the water’s edge, and with no habitation but a small Greek monastery. From Proté, a very short run, brought us to Khalki, a larger and more beautiful and well inhabited island, where I landed and took some coffee and a chibook, the enjoyment of which was much augmented by the sight of a number of young Greeks dancing in a garden on the water’s edge. I crossed from Khalki to Prinkipo in less od a quarter of an hour […].

a Greek monastery, on a hill […] was called Christos. There were two other monasteries on the island : the one called St. George, and the other St. Nicholas. St. George was situated at the peak of an elevation to the south of the island, which might merit the appelation of mountain ; the road to it from Christos was, even independent of the distant views it commanded, romantic and picturesque. On leaving the monastery amidst pinegroves, I used to descend considerably into a hollow which separates the hilly ridges of the island ; in this rocky hollow there were a few olive-trees, but it was mainly covered by brushwood, and thyme, and lavender, and other fragrant plants, among which flocks of fine large goats were seen browsing. From this hollow, a steep, irregular Alpine path ran up the sides of the mountain, with here and there a cross and a stone seat to pray or to repose ; the path terminated at a flat of confined dimensions, on which stand a group of waving trees, and a quaint-looking, ill-assorted group of buildings, the monastery and the church. The walls of the building on the side towards the Island of Marmora […] rose in several places from the edge of the precipice, and on a line with the lofty cliffs, which were almost perpendicular […]. The church was small and poor ; the interior of the monastery was chiefly of wood, and it was occupied, not by a swarm of fat, droning monks, but by a number of unfortunate Greeks who had lost their senses, attended only by a superior and three or four caloyers. It was, in short, a madhouse, and supported like the hospitals which they have at Constantinople, at Smyrna, and in most places where they reside in any number, by the donation of the Greek people, under the administration or guidance of the patriarch, or of some of their superior clergy.