Walsh, Robert (1820-1828, 1831-1835)

Entre 1820 et 1828 et entre 1831 et 1835

Né à Waterford (Irlande) en 1772, Robert Walsh fait ses études au Trinity College de Dublin. Il entre au clergé de l’Église d’Irlande et devient curé de Finglas, ville située près de la capitale irlandaise, de 1806 à 1820, période pendant laquelle il écrit une histoire de la Ville de Dublin. Il est ensuite nommé chapelain à l’Ambassade britanique de Saint-Petersbourg, puis à celle de Constantinople, conduite par le lord Strangford, où il reste plusieurs années.

Dans sa Narration de son voyage à Constantinople, Walsh dit qu’il passait régulièrement l’été dans le monastère de la Panaghia sur l’île de Chalki. On connaît la date précise d’une de ses visites (9-10 juin1823) par le récit de Benjamin Barker, qui l’accompagnait.

De 1828 à 1829, R. Walsh est chapelain à l’ambassade de Rio de Janeiro, ce qui lui donne l’occasion de voyager à travers le Brésil et de connaître les conditions de vie des esclaves. Dans ces Notices of Brazil in 1828 and 1829 il prend position en faveur de l’abolition de l’esclavage. De 1831 à 1835 il est envoyé de nouveau à Constantinople. Ayant acquis des connaissances médicales, il pratique la médecine pendant quelques années, après son retour en Irlande en 1835. En 1839 il revient à Finglas où il meurt en 1852.

(1) Texte français : R. Walsh, A residence at Constantinople during a period including the commencement, progress, and termination of the Greek and Turkish revolutions II, Frederick Westley & A. H. Davis, Londres, 1836, ch. V, p. 134-145 et 148-149, traduit par Jean-Pierre Grélois

Il y a un groupe d’îles à environ neuf milles de Constantinople dans la mer de Marmara, dans une plaisante situation non loin de la côte asiatique et, grâce à leurs charmes et à leur fertilité, à la pureté de l’air, elles sont maintenant et ont été depuis les temps de l’Empire grec, le lieu de séjour constant de riches Grecs. […] Quatre sont fertiles et habitées, cinq sont plus stériles et, bien que l’on y trouve les ruines d’édifices anciens, sont à ce jour entièrement abandonnées. Chacune est dénommée d’après une particularité et conserve son ancien nom grec. J’ai visité à différents moments […] chacune d’elles successivement et je vous les décrirai dans l’ordre où elles se présentent.

La plus proche est appelée Protè parce que c’est la première que l’on rencontre après avoir quitté le Bosphore. Elle est située à sept milles et demi de Constantinople et en fait environ trois de pourtour. Du côté est se trouve un petit village. Les penchants sociaux des Grecs sont tels qu’il n’y a que peu ou pas du tout de maisons isolées sur aucune de ces îles, mais les habitants se rassemblent tous en des endroits particuliers. L’aspect de l’île est remarquable. Elle consiste en deux éminences distinctes et égales reliées par un vallon. Sur l’une d’elle est un monastère […]

La prochaine que nous visitâmes […] était Platée, ainsi appelée du fait de sa platitude. Elle fait environ un demi-mille de pourtour et est couverte d’un épais tapis de plantes marines qui émettaient, froissées ou brisées quand nous y frayions notre chemin, une très forte et irrésistible odeur. Ces plantes servent d’abri à d’innombrables oiseaux marins, en particulier des mouettes. […]

De là nous continuâmes vers Oxie, ce que signifie bien son nom. Elle s’élève si haut qu’on la voit plus distinctement que les autres depuis la capitale, dépassant en hauteur, comme dit Gilles, les sept collines sur laquelle est bâtie ; elle est délimitée de tous côtés par des escarpements abrupts et escarpés. En approchant de son côté est la vue était très pittoresque. Une anse en demi-cercle forme une jolie baie autour de laquelle les rochers se dressent abruptement, très inégaux et romantiques. Nous fîmes chemin en montant sur les flancs et fûmes surpris de trouver qu’une part considérable des escarpements était constituée par les ruines d’édifices […]. Dans celui du bas se trouvaient les restes de citernes où l’eau de pluie, tombant sur le sommet et ruisselant sur les versants, ne cessait de s’accumuler. Le manque de sources dans cet archipel était son plus grand défaut et l’on y avait constitué des réservoirs pour l’alimentation. Deux subsistent et les Grecs utilisent toujours ces citernes de leurs ancêtres. […] Montés plus haut nous nous trouvâmes sur une plateforme qui semblait être les ruines d’une chambre dont une moitié était tombée dans le précipice sur lequel elle avait été bâtie, et l’autre subsistait en formant un demi-cercle. Nous en prîmes possession et préparâmes dans ce vestige du palais des empereurs notre petit déjeuner et fîmes notre thé avec l’eau de leur citerne. De là nous gravîmes un étroit sentier qui se déploie en spirale autour de l’île, cheminant partout entre des murs bâtis de briques plates liées par un mortier de chaux et de tuileau. De petites citernes étaient disséminées à travers toutes les ruines ; l’une d’elles se dressait comme une cheminée au point culminant de l’île, et ressemblait à un entonnoir renversé dont la partie large qui devrait se déployer pour recevoir l’eau se trouvait en bas […]

Nous descendîmes de ce rocher de ruines qui semblait avoir été la prison aussi bien que la retraite des empereurs grecs, […] et nous passâmes au-delà de la petite île de Pite, ainsi appelée du fait de l’abondance de pins qui jadis la couvraient, bien qu’elle soit maintenant presque entièrement nue, et de là à Antigone, distante d’environ un mille. Zônaras dit qu’elle portait auparavant le nom de Panormos, mais ne dit pas pourquoi il fut changé en Antigone. Elle s’élève en une seule éminence sur laquelle du temps de Gilles se dressait un monastère qui subsiste aujourd’hui. Elle fait environ trois milles de pourtour, avec un village du côté est entouré de vignes. Nous y rencontrâmes l’excellent et lettré archevêque du Mont-Sinaï […]. Il avait écrit en grec moderne un ouvrage statistique sur Constantinople, rendant compte de son état ancien et présent […]. Il avait […] envoyé l’ouvrage à Venise pour qu’il y soit imprimé et attendait un temps plus favorable pour sa publication [Il s’agit de Kônstantios, Κωνσταντινιάς, Venise 1824 (n. d. t.).] […]

De là nous continuâmes vers Chalkitis ou, comme elle est nommée par les Grecs modernes, Chalki d’après chalkos, le cuivre qui y abondait jadis. […] L’île présente des signes évidents de cette présence. Nous rencontrâmes des amoncellements de galets marqués de teintes variées de vert et de bleu, apparemment de quelque oxyde de cuivre, ce qui semblait être la cyanose mentionnée par des auteurs antiques. Dans l’un des vallons, là où la mer forme une baie délicieuse, se trouvent des signes évidents que des mines y avaient été jadis exploitées. On trouve encore de grands amoncellements de déblais rejetés des galeries, et de scories de fourneau dans l’état où les avaient laissés les Grecs du Bas Empire. C’est ici que Gilles ramassa ce qu’il appelle de la cyanose et de la chrysocolle : en fait tout se trouve en cet endroit dans l’état où il le décrit, et atteste la précision générale de ses comptes rendus. Les amoncellements qu’il mentionne sont constitués de pierres avec des incrustations de cuivre aux diverses nuances de bleu, et des scories à différents degrés de calcination et de vitrification. […] Quelques puits dans le vallon ont [une eau] fortement imprégnée d’un goût métallique et d’une couleur azurée et on ne l’utilise que pour l’irrigation.

Le dessin de l’île est très remarquable. Elle présente trois éminences distinctes. Sur le sommet de l’une d’elles se trouve le monastère de la Trinité, jadis très étendu, mais pour sa plus grande partie incendié. Le côté contenant l’église est intact. Il y a dans le porche une grande et curieuse peinture du Jugement Dernier. Au sommet se trouve la Divinité vêtue de somptueux vêtements, portant une couronne royale. Devant Lui est le livre ouvert par des chérubins, comme un long livre de musique qui s’étend d’un côté à l’autre de la peinture, contenant la sentence finale pour chacun. Il y a là Abraham avec Lazare dans son sein, comme un enfant dans les bras de sa nourrice ; ailleurs le voleur repenti avec une croix sur l’épaule qui paraît avoir froid et être misérable. À gauche se trouve une représentation de l’Enfer, la gueule d’une grande bête qui avale les méchants par milliers, tandis que les diables les jettent de haut en bas. Parmi eux sont les traîtres et persécuteurs des chrétiens. Celui qui attire le plus l’attention est Judas, avec sa bourse, qui se démène dans la foule ; vient ensuite Dioclétien à la contenance pleine de remords. On nous suggéra que Mahmut, l’actuel sultan, lui serait adjoint quand il serait sûr de le faire. L’artiste a imité la satire de Léonard de Vinci dans sa Cène et inséré un individu qui lui était personnellement hostile, car il a introduit parmi les damnés un drogman de la Porte, avec son kalpak et autres signes distinctifs, avec qui il avait eu une querelle. Je note ces particularités de cette peinture parce que mon attention avait été attirée sur elle à Constantinople, en tant qu’un chef-d’œuvre artistique, et l’une des plus remarquables que l’on trouve dans toute l’Église grecque. Quant au nom de l’artiste et à l’époque où il fleurissait, les caloyers ne purent nous en informer. L’église elle-même est dédiée à saint Georges qui est représenté à cheval transperçant le dragon de sa lance, exactement comme chez nous. À côté du monastère se trouve un kiosque avec une vue magnifique sur l’ensemble de l’archipel. C’est une annexe générale de tous ces établissements religieux, une sorte de café où les moines servent des pipes et du café aux étrangers qui les paient comme partout ailleurs. Le costume dans ce monastère, comme en général dans les autres, est une ample et mince robe de coton bleu léger.

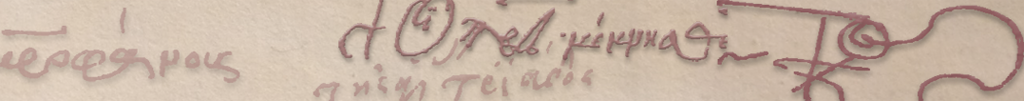

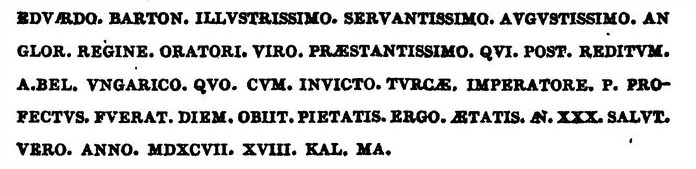

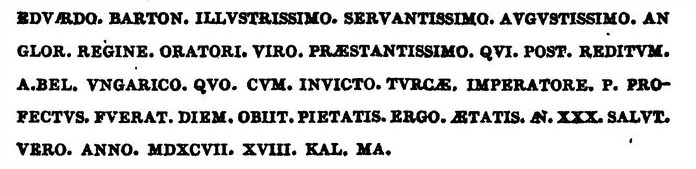

Sur la colline opposée se trouve un autre monastère dédié à la Panaghia, la Vierge. Nous y montâmes par une large route, la seule qui prétende à ce nom que j’aie vu en Turquie. Comme nous cheminions en tournant vers le sommet, il se présentait à nous de beaux tableaux variés du paysage environnant. La route était bordée de taillis de myrte et d’arbousier, semés de bouquets de jeunes pins, au milieu desquels jaillissait le bâtiment du monastère. Celui-ci ne se distinguait pas par une peinture, mais par un objet beaucoup plus intéressant. Notre premier ambassadeur résident, Sir Edward Barton, s’était retiré sur cette île pour restaurer sa santé et, y étant mort, fut enterré ; une tombe avec une inscription fut élevée au-dessus de lui. La tombe se dressait encore au temps de Dallaway en 1797 ; avec le temps elle se délabra et la pierre portant l’inscription fut déplacée. Son Excellence Lord Strangford exprima le vœu de la trouver et de réédifier la tombe d’une façon convenable, en l’entourant d’une clôture de fer, à la place où elle se dressait à l’origine, au-dessus de l’endroit où les restes du défunt avaient été déposés. Il me donna mission de m’informer sur l’une et d’enquêter sur l’autre. Les caloyers nous montrèrent les deux. L’[emplacement de la tombe] était dans le bouquet de pin à côté du monastère, et ils me désignèrent du doigt la [pierre tombale] dans l’arcade du portail d’entrée, immédiatement au-dessus de la porte. Elle est insérée de côté dans la maçonnerie, mais les lettres sont intactes et très lisibles. La voici :

[Cette transcription présente quelques différences avec ce que l’on voit sur l’illustration insérée entre les p. 142 et 143 de l’édition]

Fig.: Pierre tombale d'un ambassadeur britannique sur le mur d'un monastère de l'île de Chalki

Je pensai que rien ne serait plus nécessaire que de donner des instructions pour la remettre à sa place d’origine ; mais je trouvai qu’il serait nécessaire, du fait qu’elle était devenue une partie constitutive du monastère, d’obtenir du sultan un firman pour la déposer, puisqu’aucune pierre ne peut être déplacée d’aucun édifice religieux grec sans une telle permission, ni en payant une forte somme. N’étant pas disposé à [faire] l’un ou l’autre, je fus obligé de différer jusqu’à une autre occasion.

Deux longues avenues de magnifiques cyprès, se terminant en angle et divergeant en ligne droite, mènent à une résidence princière sur le rivage, près de la localité. C’était anciennement le palais, comme nous en fûmes informés, de Mavrogénès, un prince grec qui avait une situation dans l’armée durant la dernière guerre avec les Russes. Il fut décapité sur ordre du vizir pour un prétendu délit, ce qui exaspéra tant le sultan qu’il fit décapiter le vizir et son fils, en sacrifice à ses mânes. […] Elle servait alors de résidence d’été au baron Ottenfels, l’internonce autrichien.

De Chalki nous traversâmes jusqu’à Prinkipo, la plus grande et la plus peuplée des îles, ce qui leur vaut l’appellation moderne. C’est la plus éloignée de la capitale […]

Elle fait environ huit milles de pourtour, avec une localité du côté est, contenant environ 300 habitants. Le long du rivage se trouvent les restes d’un très vaste monastère où résidaient jadis cinquante nonnes. Il y en a un autre sur l’une des collines, mais dans un grand état de délabrement. Il est dédié à la Transfiguration et ne compte qu’un seul moine. Il y en a un autre sur la plus haute éminence de l’île, dédié à saint Georges et hautement réputé pour sa sainteté.

L’usage d’exorciser les possédés du démon existe toujours dans l’Église grecque. Dans de nombreuses se trouvent des pitons munis d’anneau enfoncés dans le sol devant l’autel, avec des chaînes qui y sont passées. On y mène les fous furieux et on les enchaîne, puis l’office de l’exorcisme est exécuté au-dessus d’eux. […]

À côté de Prinkipo se trouvent deux îles, comme des satellites accompagnant une grande planète. L’une est appelée Néandre, l’autre Antirovithe. Elles sont inhabitées et n’offrent rien de remarquable, sinon que la seconde est appelée l’île des Lapins, dont elle abondait jadis. […]

Par une sorte de prescription, aucun Turc n’a le droit de résider ici, de sorte que, exception faite de quatre ou cinq qui sont envoyés à titre officiel, on n’en voit jamais. La population est tout entière grecque (avec quelques Francs), s’élevant à environ 800 [habitants], y compris ceux de Prinkipo mentionnés plus haut. […]

Je passais ordinairement l’été dans l’île de Chalchi, dans la mer de Marmara, et je logeais dans un grand couvent, auprès duquel était le tombeau de Sir Ed. Barton, le premier ambassadeur anglais à Constantinople qui y soit mort pendant sa mission ; ce tombeau, par la suite des temps, avait été dilapidé, et la pierre sur laquelle se trouvait son épitaphe avait été placée sur la grande porte du couvent. Lord Strangford voulut que ce tombeau de l’un de ses prédécesseurs fût rétabli, et il me chargea de ce soi. Je m’occupai d’accomplir ses ordres ; mais, dès que je m’adressai aux caloyers, ou moins de ce couvent, je reconnus que je rencontrerais de grands obstacles. Comme la pierre dont je viens de parler avait été placée sur le mur, elle faisait alors partie de l’édifice, et ne pouvait plus en être ôtée sans une permission expresse, ou sans s’exposer à une amende considérable. Cette permission ne m’aurait pas été refusée ; mais son excellence ayant quitté Constantinople sur ces entrefaites, la pierre tumulaire de notre ambassadeur est restée au-dessus de la porte d’un couvent grec.

(3) Texte français : Constantinople and the scenery of the seven churches of Asia minor, illustrated in a series of drawings from nature by Thomas Allom, with an historical account of Constantinople, and description of the plates by the rev. Robert Walsh, LL.D., Chaplain to the British embassy at the Ottoman Porte, second series, London & Paris [1838], p. 20-26 [manquent les pp. 22-23] (autre numérisation [manquent les pp. 25-26]), traduit par Jean-Pierre Grélois

LES ÎLES DES PRINCESSES

Les deux détroits par lesquels on arrive à Constantinople sont marqués à leur entrée par des groupes d’îles. Avant d’entrer dans les Dardanelles, le voyageur passe par les Cyclades ; aux abords du Bosphore il se trouve dans un groupe semblable qui forme l’archipel de la Propontide qui, s’il n’est pas aussi étendu, est pourtant plus charmant que celui de l’Égée.

Les Cyclades de la Propontide étaient anciennement appelées Dèmonèsia, ou « îles des Esprits » ; mais elles prirent sous le Bas-Empire une autre dénomination ? Irène, la veuve de Fl. Léon, avait fait aveugler son fils pour qu’elle puisse régner elle-même à sa place ; elle fut pour cette raison bannie par son successeur sur ces îles. Comme elle avait édifié sur l’une d’elles, pour racheter ses fautes, un monastère et des bâtiments où les filles de la famille impériale recevaient une éducation, l’archipel fut appelé après elle les « îles des Princesses ». Elles sont au nombre de neuf et ont chacune un nom grec qui rappelle quelque particularité. Les quatre plus petites sont inhabitées ; elles sont situées entre les côtes de l’Europe et de l’Asie, à environ 10 milles de chacune, et à la même distance de l’embouchure du Bosphore […].

Les îles souffrent de deux inconvénients. L’un est le manque d’eau : il n’y a pas de cours d’eau et les sources y sont saturées d’éléments minéraux qui se trouvent partout dans le sol, en particulier sur l’île de Chalki. Pour y remédier, les maisons, en particulier les monastères, disposent de profondes fosses constituant des réservoirs qui reçoivent l’eau de pluie ; ce dépôt est si sacré que les margelles sont couvertes avec des opercules de fer soigneusement fermés à clef, et seulement ouvert avec précaution à des moments désignés. Sur les îles désertes plus petites, il existe des citernes datant des temps anciens, d’où les navires de guerre et de commerce de passage tirent de l’eau.

Le second est causé par les ouragans soudains auxquels elles sont sujettes par le plus calme et le plus beau des temps. […]

Les îles sont excessivement belles et salubres : à la différence de leurs parentes de l’Égée, il n’y a rien de dénudé ou de rocailleux dans leur aspect. Elles sont généralement couronnées d’arbousiers, de pins, de cyprès, de myrte et de différentes espèces de chênes, en particulier le kermès qui garde ses feuilles immuables en toutes saisons et rend les îles verdoyantes et romantiques en tous temps. […] Il y a en outre une variété d’autres arbres qui, bien qu’à feuilles caduques, perdent rarement leur feuillage ; tel est le térébinthe qui exhale un arome résineux […]. Mais les buissons qui abondent le plus sont les variétés de ciste à gomme qui couvrent de vastes espaces et parfois teintent la surface des collines au point que les îles sont colorées de la riche nuance de leurs fleurs éclatantes. […]

Pendant la révolution grecque, ces îles servirent de prison pour les suspects. […] Parmi les suspects enfermés dans l’une de ces prisons insulaires se trouvait le vénérable et lettré archevêque du Mont-Sinaï. […] Il était occupé à un ouvrage sur l’état ancien et moderne de Constantinople, et son seul vœu était […] qu’il lui fût permis de vivre et de le terminer. Contrairement à ses attentes, ses souhaits furent exaucés. […]

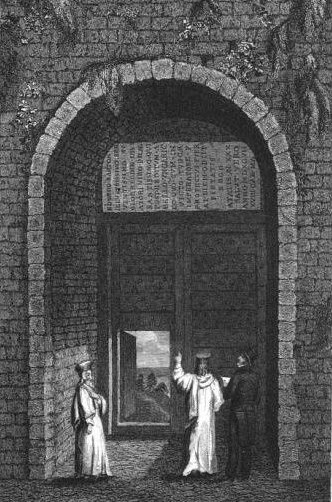

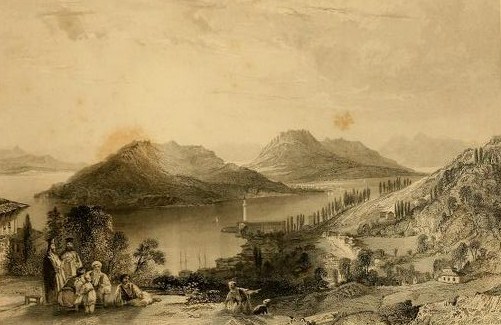

Fig. Les Îles-des-Princes depuis le monastère de la Trinité. À mi-distance, Prinkipo.

La vue sur notre illustration est prise depuis le monastère de la Trinité dans l’île de Chalki. Cet édifice fut fondé par le patriarche Phôtios […]. Le présent édifice, habité par les caloyers, n’est qu’une aile du bâtiment d’origine. Au premier plan sur un replat, se trouve un kiosque d’où l’on a l’une de ces vues charmantes que présente presque chaque éminence de l’île. À chaque monastère est attaché un tel édifice ; c’est une sorte de café ouvert aux étrangers pour qu’ils s’y reposent et profitent de la beauté du paysage ; on les voit avec des pipes, du café et des douceurs servis par les bons moines. La vue depuis ce kiosque de la Trinité est particulièrement vantée et décrite par l’archevêque […]

Juste au-dessous s’expose le visage varié de l’île, avec ses buissons et ses arbres. Une allée de gigantesques cyprès conduit, par la crête d’une colline en pente, vers un édifice sur le rivage ; il avait été construit par un riche çelebi grec aux jours heureux de sa prospérité. Il fut suspecté, arrêté et exécuté, et sa splendide résidence, qui contenait tout ce qui convient au luxe grec moderne, fut occupée par divers Francs qui quittaient les chaleurs suffocantes de la capitale pour les brises rafraîchissantes des îles. Le long du rivage courent les rues du chef-lieu de Chalki, avec sa flottille de petites embarcations mouillées dans le port. Parmi les édifices il en est certains qui présentent une vue inhabituelle dans ces îles. Sur un promontoire un minaret dresse sa pointe effilée, et sur la colline derrière se trouve un kışla, ou caserne turque. Quand l’insurrection eut éclaté, les immunités des îles furent supprimées et l’on voit maintenant des édifices et des gens musulmans mêlés à la population jusque là exclusivement grecque.

LE MONASTÈRE SAINT-GEORGES DU PRÉCIPICE

Il n’est pas de saint du calendrier oriental qui soit tenu en plus haute estime, à la fois par les musulmans et les chrétiens, que saint Georges de Cappadoce. […] Cette légende […] est rappelée dans cette église Saint-Georges par une peinture du porche : le saint est représenté à cheval, transperçant de sa lance un dragon ailé […].

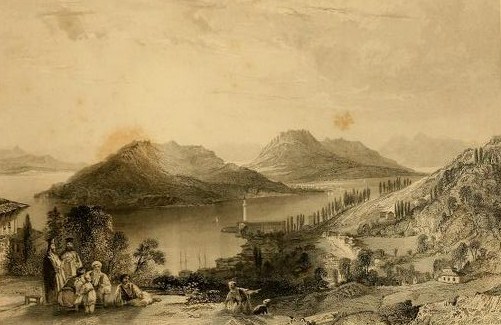

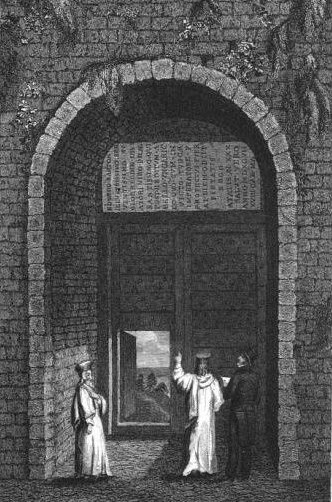

Fig.: Monastère de Saint-Georges-du-Précipice (Îles-des-Princes) [En fait, il s'agit de Saint-Georges de Chalki]

Dans l’église du monastère se trouve une peinture hautement prisée en tant que chef d’œuvre de l’art grec ; elle représente le Jugement Dernier, un sujet favori des moines grecs pour impressionner leurs ouailles. Sur certaines, les châtiments […] sont à peine regardables […]. Cette peinture est pourtant moins répréhensible ; elle représente au sommet la Divinité, vêtue de manteaux somptueux et couronnée comme un roi, tenant devant Elle un livre ouvert dans lequel est enregistré le sort de chaque mortel ; plus bas il y a d’un côté un jardin divisé en divers compartiments comme des bancs d’église, dans chacun desquels est enfermé un personnage célèbre. Dans l’un, Abraham avec Lazare dans son sein ; dans un autre le larron repenti avec sa croix sur l’épaule. Immédiatement au-dessous se trouve les machoires grand ouvertes d’un immense monstre, dans lesquelles des démons jettent les âmes des damnés, parmi qui il y a tous les apostats et persécuteurs de la Chrétienté, Judas, Julien et Dioclétien, avec divers Turcs. Parmi les damnés on a la surprise de voir un Grec avec son kalpak ; ç’avait été un drogman de la Porte qui avait offensé l’artiste, et ce dernier usa de ce moyen non sans précédent de se venger de son adversaire.

There is an archipelago of islands lying about nine miles from Constantinople in the Sea of Marmora, very pleasantly situated a short distance from the Asiatic coast, and from their amenity and fertility, and the purity of the air, are now, and have been since the time of the Greek empire, the constant resort of opulent Greeks. […] Four are fertile and inhabited, five are more sterile, and though there are found on them the remains of former edifices, are at this day altogether abandoned. They are each denominated from some local circumstance, and still retain their ancient Greek names. I visited at different times […] each of them in succession, and I shall describe them to you in the order in which they stand.

The nearest is called Proté, from being the first met with after leaving the Bosphorus. It lies seven and a half miles from Constantinople, and is about three in circumference. On its eastern side is a small village. The social propensities of the Grreks are such, that there are few or no detached houses on any of the islands, but the inhabitants all congregate together in particular spots. The appearance of the island is remarkable. It consists of two distinct and equal heads joined together by a valley. On one of them is a monastery […].

The next we visited […] was Platé, so called from its flatness. It was about half a mile in circumference, and covered with a thick matting of marine plants, which, when bruised by being trampled on, or broken by forcing our way through them, emitted a very stron and overpowering odour. These plants are the cover of innumerable sea-fowl, particularly gulls. […]

From hence we proceeded to Oxea, which its name well designates. It rises so high, that it is more distinctly seen from the capital than the rest, out-topping, as Gillius says, the seven hills on which it is built, and it is surrounded on all sides by sharp, steep precipices. On approaching the east side, the view was very picturesque. A semicircular bend formed a fine bay, around which the rocks rose abruptly, very rugged and romantic. We made our way up the sides, and were surprised to find a considerable portion of the precipices was formed by the ruin of edifices […]. Among the lowest were the remains of cisterns, into which the rain-water, falling on the summit and trickling down the sides, was continually deposited. The want of springs in this archipelago was its greatest defect, and here were formed reservoirs which supplied them. Two yet remain, and the Greeks still use those cisterns of their progenitors. […] On ascending higher we stood on a platform, which seemed the ruins of a chamber, one half of which had fallen over the precipice on which it was built, and the other remained forming a semicircular section. Of this we took possession, and in this remnant of the palace of the empereors we prepared our breakfast, and made our tea with the water of their cistern. From hence we ascended by a steep path, winding spirally round the island, and everywhere made our way through walls built of flat bricks, cemented with a mortar made of lime and pounded tiles. Through all the ruins were dispersed small cisterns ; one so called stood like a chimney, on the highest point of the island, and resembled an inverted tundish, the broad part which should expand above to receive the rain being below. […]

We descended from this rock of ruins, which it seems was the prison as well as the retreat of the Greek emperors, […] and we passed over to the little island of Pitya, so called, from the abundance of pine which once covered it, though now nearly denuded ; and from thence to Antigone, distant about one mile. Zonaras says it was formerly called Panormus, but does not tell why it was changed to Antigone. It rises on a single eminence, on which stood a monastery in the time of Gillius, which yet remains. It is about three miles in circumference, with a village on the east side, surrounded by vineyards. Here we found the excellent and learned Archbishop of Mount Sinai, […] he had written a statistical work on Constantinople in modern Greek, countaining an account of its ancient and present state […]. He had […] sent the work to Venice to be printed, and awaited a more favourable time for its publication. […]

From hence we proceeded to Calcitis, or as it is called by the modern Greeks, Chalki, from χαλκός, brass, in which it formerly abounded. […] The island bears evident marks of this metallic state. We met heaps of pebbles stained with various tints of green and blue, apparently from some copper oxide, and which appeared to be the cyanus mentioned by ancient writers. In one of the valleys, where the sea forms a delightful bay, are evident marks that mines were once worked. Large heaps of waste thrown out from the shafts and scoriæ from furnaces are fond still in the state in which they were left by the Greeks of the Lower Empire. Here it was that Gillius gathered what he calls cœruleum and chrysokolla ; and in fact everything in this spot is exactly in the state in which he describes it, and attests the general accuracy of all his acounts. The scrobes or heaps he mentions consist of stones with copper incrustations of various shades of blue, and slags in different stages of calcination and vitrification. […] Some wells in the valley are strongly impregnated with a metallic taste and of an azure hue, and are used only for the purpose of irrigation.

The contour of the island is very remarkable. It forms a triceps, or three distinct heads. On the summit of one of them is the Monastery of the Triades, or Trinity, once very extensive, but the greater part of it burnt down. The side containing the church is perfect. In the porch is a large and curious picture of the Last Day. On the summit is the Deity dressed in sumptuous robes, and crowned like a king. Before him is the book opened by cherubims, like a long music-book, extending from side to side of the picture, containing the final sentence of every individual. In one is Abraham, with Lazarus in his bosom, like a child in a nurse’s arms ; in another is the penitent thief, with a cross on his shoulder, looking very cold and miserable. On his left is a representation of hell, depicted by the mouth of a great beast, who is swallowing the wicked by thousands, as the devils throw them down to him from above. Among them are the traitors and persecutors of Christianity. The most conspicuous of the first is Judas, with his bag, struggling in the crowd ; and of the second, Diocletian, with remorse in his countenance. It was intimated to us, that Mahmood, the present Sultan, would be joined with him when it will be safe to do so. The artist has copied the satire of Leonardo da Vinci in his Last Supper, and inserted an individual who was personally hostile to himself, for he has introduced among the damned a dragoman of the Porte, with his calpac and other designations, with whom he had a quarrel. I notice the particulars of this picture because my attention was directed to it at Constantinople as a chef-d’œuvre of art, and one of the most distinguished to be found in the whole of the Greek church. The name of the artist, and the time in which he flourished, the caloyers could not inform us. The church itself is dedicated to St. George, who is represented on horseback, piercing the dragon with his spear exactly as he is with us. Beside the monastery is a kiosk commanding a magnificent prospect of the whole of the archipelago. This is a general appendage of all such religious establishements. It is a kind of coffeehouse, where strangers are served with pipes and coffee by the monks, which they pay for as in any other. The costume of this convent, as generally of all the rest, is a thin loose robe of light blue cotton.

On the opposite hill is another convent dedicated to the Panaya, or Virgin. We ascended to it by a broad road, the only one that had the pretensions to the name that I had seen in Turkey. As we wound up it towards the summit, it presented us with various and beautiful pictures of the surrounding scenery. The road was skirted with copses of myrtle and arbutus, interspersed with groves of young pines, and from the centre of them issued the building of the monastery. This was not distinguished by a picture, but by a much more interesting object. Our first resident ambassador, Sir Edward Barton, had retired to this island for the restoration of his health, and having died here, he was buried, and a tomb, with an inscription, erected over him. The tomb was still standing in the time of Dallaway, in 1797 ; in process of time it had been dilapidated, and the stone containing the inscription carried off. It was his Excellency Lord Strangford’s wish to have it found, and the tomb re-erected in a suitable manner, and surrounded with iron railing, in the place where it originally stood, over the spot where the remains of the deceased were deposited ; and he commissioned me to ascertain the one, and to make inquiry after the other. The caloyers showed them both to us. The first was in the pine grove beside the monastery, and they pointed out to me the second in the archway of the gate of entrance, immediately over the door. In repairing the edifice, they took the first stones that came to their hands, and this afforded a convenient one. It is inserted in the wall on its side, but the letters are still perfect and very legible. It is as follows : —

Fig.: Tomb stone of a British ambassador in the wall of a convent in the island of Chalki.

I thought nothing more would be necessary than to give directions to have it replaced in its former side ; but I found, as it had now become part and parcel of the convent, it would be necessary to have the Sultan’firman to have it taken down, as not a stone can be displaced in any religious edifice of the Greeks without such permission, and paying a large sum for it ; not being prepared for either, I was obliged to defer it till another opportunity

Two long avenues of magnificent cypress, terminating at an angle, and diverging in right lines, lead to a princely residence on the sea-shore, near the town. This was formerly the palace, we were informed, of Mavroyeni, a Greek prince, who had a situation in the army of the Grand Vizir in the last Russian war. He was decapitated by the Vizir for some alleged deliquency, which so exasperated the Sultan that he decapitated the Vizir and his son as a sacrifice to his manes. […] It was now occupied as a summer residence by Baron Ottenfels, the Austrian internuncio.

From Chalki we crossed over to Prinkipo, the largest and most populous of the islands, and from which they take their modern appellation. It is the most distant from the capital. […]

It is about eight miles in circumference, with a town in its east side, containing about three hundred inhabitants. Along the shore are the remains of a very extensive convent, which once contained fifty nuns. On one of the hills is another, but in a great state of disrepair. It is dedicated to the Transfiguration, and contains but a single monk. On the highest eminence of the island is another, dedicated to St. George, in high repute for its sanctity.

The practice of exorcising demoniacs is still in use in the Greek church. In many of them are bolt-rings sunk in the floor before the altar, with chains passed through them. To these the maniacs are led and chained, and the service of exorcism is performed over them. […]

Beside Prinkipo are two islands, attending like satellites on a great planet. One is called Neandros, and the other Antirovithi. They are uninhabited, and remarkable for nothing, except that the latter is called the Island of Rabbits, with which it once abounded. […]

By a kind of prescription, no Turk is permitted to reside here ; so that, with the exception of four or five who are sent officially, they are never seen. The whole population is Greek, with a few Franks, amounting to about eight hundred, including those of Prinkipo, whom I have mentioned.

[2] Texte anglais : R. Walsh, Narrative of a journey from Constantinople to England, Frederick Westley & A. H. Davis, Londres,1828, p. 127 (autre édition: Philadelphia, 1828, p. 83)

I usually passed the summer in the island of Chalchi, in the Sea of Marmora; and lodged in a large monastery, near which stood the tom of Sir Ed. Barton, the first English resident ambassador at Constantinople, who died there during his mission. His tomb, in the lapse of time, had been dilapidated, and the stone containing the inscription taken and placed, as a convenient flag, over the gate-way of the convent. It was his Excellency Lord Strangford’s desire that this venerable monument of his predecessor should be re-edified, and he commissioned me to see it done. I proceeded immediately to execute his whishes; but on applying for that purpose to the caloyers, or monks of the convent, I found it could not be so speedily accomplished; as it was now in the well, it made a part and parcel of the convent, from which a stone could not be moved without permission, under a heavy penalty. This permission would not have been withheld; but before it was obtained his Excellency left Constantinople, and our ambassador’s tomb-stone still remains, I believe, over the gate-way of a Greek.

(3) Texte anglais : Constantinople and the scenery of the seven churches of Asia minor, illustrated in a series of drawings from nature by Thomas Allom, with an historical account of Constantinople, and description of the plates by the rev. Robert Walsh, LL.D., Chaplain to the British embassy at the Ottoman Porte, second series, London & Paris [1838], p. 20-26 [manquent les pp. 22-23] (autre numérisation [manquent les pp. 25-26]).

THE PRINCESS' ISLANDS

The two straits by which Constantinople is approached, are marked at their entrance by clusters of islands. The traveller, before he enters the Dardanelles, passes through the Cyclades; as he approaches the Bosphorus, he finds himself among a similar group, forming an Archipelago in the Propontis, if not so extensive, yet still more lovely than that in the Egean.

The Cyclades of the Propontis was anciently called Demonesca, or the "islands of spirits;" but under the Lower Empire they assumed another denomination. Irene, the widow of Fl. Leo, had put out the eyes of her son, in order that she herself might reign in his place; for this she was banished by his successor, to these islands; and, having built a monastery on one of them, to atone for her guilt, and erected edifices where females of the imperial family were educated, the group was called, therefore, after her, the "Princess' Islands." They are nine in number, of different sizes, and are distinguished by Greek names, indicating some peculiarity of each. [* The names were as follow: Prote, because it is the first met in sailing from Constantinople— Chalki, from its copper mines—Prinkipo, the residence of a princess—Antigone, so called by Demetrius Polyorcetes in memory of his father Antigonus—Oxy, from its sharp precipices—Platy rom its flatness—Pitya, from its pines, &c.]

The four smaller are uninhabited ; they lie between the European and Asiatic coasts, about 10 miles from each, and the same distance from the mouth of the Bosphorus; and to the houses of the streets built on the eminences, both of Pera and Constantinople, exhibit a picturesque and striking prospect.

The water which flows round them is not less pure than the air is balmy; they seem to float in a sea of singular transparency, so clear and lucid that objects are distinctly seen at the greatest depths; and the caique which glides over it seems supported by a fluid less dense than water, and nearly as invisible and transparent as air. From various circumstances, it is conjectured that the islands were originally one mass, and torn asunder by some convulsion of nature; abrupt promontories in the one correspond with bays and indentations in the opposite, and the space between is so deep, that the large ships of Admiral Duckworth's fleet anchored everywhere among them with perfect safety, when they passed into the Propontis, to menace the capital. Fish of many kinds abound in the streights, and their capture is one of the employments and amusements of the residents. The fishing carried on by night is very picturesque. The boats proceed with blazing faggots lighted in braziers of iron projecting from their bow and stern; and at certain times the shores are illuminated every night, by innumerable moving lights floating round them.

The islands labour under two disadvantages; one is, the want of water: there are no streams, and the springs found are impregnated with mineral ingredients, everywhere mixed up with the soil, particularly in the island of Chalki. To remedy this, the houses, and particularly the convents, have deep excavations, forming reservoirs into which the rain is received; so sacred is this deposit, that the wells are covered with iron stopples, carefully locked, and only opened with great caution at stated times. On the smaller deserted islands, deep cisterns of former times exist, where passing ships and boats at this day draw up water.

The next is, the sudden hurricanes to which they are subject in the most calm and beautiful weather. The air seems to stagnate, and a death-like stillness succeeds; then a dark lurid spot appears near the horizon, which suddenly bursts, as it were, and an explosion of wind issues from it, which sweeps everything before it. The doors and windows of the houses are instantly burst open, and every thing on land seems splitting to pieces; the sea is raised into mountains of white foam; and the only hope of safety for ships is to drive before it. The boats of the islands are sometimes overtaken thus in their passage to the capital: the boatmen at once lose all power of managing their caiques, and throw themselves on their faces in despair, crying out "For our sins, for our sins!" In this state the vessel turns over, and goes down with all her passengers. Accidents of this kind happen every year.

The islands are exceedingly beautiful and salubrious; unlike many of their kindred in the Egean, there is nothing bare or rugged in their aspect. They are generally crowned with arbutus, pine, cypress, myrtle, and different kinds of oak, particularly the kermes or evergreen, so that they preserve their leaves unchanged at all seasons, and render the islands at all times verdant and romantic. The arbutus grows with such luxuriance, that it ripens its berries into large mellow fruit, which is sold in the markets, and furnishes a rich dessert; they are eaten as strawberries, which they nearly resemble in shape, colour, and taste. There are, besides, various other trees, which, though deciduous, seldom lose their foliage; such as the terebinth or cypress turpentine, which yields a resinous aroma, so that a stranger, in making his way through these romantic thickets, as he presses aside the branches, is surprised at the grateful odours exhaled about him : but the shrubs which most abound, are the various species of the gum-cistus; they cover large tracts, and sometimes so tint the surface of the hills, that the islands are suffused with a rich hue from their bright blossoms. The fragrance of these spots is exceedingly rich and grateful. As the traveller moves through the low shrubs, and disturbs them with his feet, a dense vapour of odoriferous particles ascends, and the air seems loaded, as it were, with a palpable fragrance.* [* The gum-resin, yielded by these plants, is sometimes collected by combing the beards of the goats, which browse among them, when they return home at night; and sometimes a leather thong is drawn across them, and that which adheres scraped off. The boots of those who walk through the shrubs are often incrusted with this gum.] This gratification of the senses has conferred upon the islands the character of luxurious enjoyment, which has at all times distinguished them; they were, therefore, considered the Capreae of the Lower Empire, and became the Capua of the Turks; when their rude military energy degenerated, they retired here, to gratify themselves with indulgences which were prohibited even in the license of the capital. Whenever the plague rages, they are crowded with Frank and Raya fugitives, who escape to this asylum from the pestilential atmosphere of the city.

By a prescription, some time established, the islands have been entirely abandoned to the Greeks, and no Turk is allowed to take-up his residence there, except temporarily, on official business. Even the aga who superintends them, resides on the opposite coast of Asia, and never visits them except to collect the haratch. No mosque or other Moslem edifice was allowed to raise its crescent-head; but the larger islands had one or more Greek monasteries crowning their summits, and forming the most conspicuous objects. They were erected in the time of the Lower Empire, and were the asylums to which the sovereigns retired when compelled to abdicate the throne: many of them were the retreats of those who were mutilated or blinded by their successors; many were the receptacles where guilt and remorse sought, by solitude and penance, to atone for past crimes. Some of these monasteries are now in ruins, and their "ivy-mantled towers" add to the picturesque scenery; some are still kept in good repair, and the residence of Caloyers, having chapels eminent for their sanctity, to which not only the people of the islands, but many families of the Fanal, resort, and celebrate their festivals with much pomp and devotion.

On the greater islands are towns called by the same names. They possess fleets of caiques of a larger size than ordinary, which keep up a daily communication with the capital in conveying goods and passengers. Every morning these fleets leave the islands at sunrise, and return by sunset. The merry disposition of the people is nowhere more displayed than in these passage-boats, which the gravity and taciturnity of a Turk, who is an occasional passenger, cannot suppress. It sometimes happens that this levity is severely punished: on a charge of some real or supposed delinquency, the crews are cited before the cadi, when they land at Tophana. His carpet is spread on the ground, and where he sits cross-legged smoking his nargillai, the laughing culprits are brought before him, and he dispenses justice in a summary manner. He waves his hand—the delinquent is seized by two men who throw him on his back, while two more raise his feet between poles, presenting their soles. Executioners then, provided with angular rods as thick as a man's thumb, lay on the shrieking wretch till he faints, or the cadi, by another wave of his hand, intimates to them to cease: this punishment of the unfortunate caique-gees of the islands, is very frequent, and sometimes is inflicted on the whole of the boats' crews. It often happens to be so severe, that the legs swell as high as the hips, and the victim is in danger of dying of a mortification; notwithstanding, it is soon forgotten by the sufferers. On their return, they only laugh at each other, and the next day repeat the fault for which they were punished.

During the Greek revolution, these islands were made the prison of the suspected. The families of the Fanal were sent here, to be kept in safe custody till their fate was decided in the capital; every day some unfortunate victim was taken away, and never re-appeared, yet this seemed to make little impression on the survivors. They were constantly seen in groups under some favourite trees, playing dominos, chess, or other games, and entering with as much earnestness and disputation into the chances, as if they were in a state of perfect security- Sometimes a caique was seen approaching, and the turbaned head of a chaoush appeared over the gunwale—he landed, approached the groups of players, and laid a black handkerchief on the shoulder of one of them ; the doomed man rose from his seat, followed the chaoush to the caique, and never returned again. His place was supplied by another, and the game was continued as if nothing extraordinary had happened. The bouyancy and reckless character of the Greeks, during the perils of their revolution, wras nowhere, perhaps, so displayed as on these occasions; they saw their friends daily taken from the midst of them, and knew they were led away to be strangled or decapitated, yet it seemed but little to affect the careless hilarity of the daily decreasing survivors.

Among the suspected shut up in one of these insular prisons was the venerable and learned archbishop of Mount Sinai. After the execution of the patriarch and his prelates, he hourly expected his mortal summons; yet it never affected his cheerfulness: he was engaged in a work on the ancient and modern state of Constantinople, and his only wish, unfounded then on any hope, was, that he might be allowed to live and finish it. His wishes, contrary to his expectations, were fulfilled. I left him in his Patmos, every day looking for death; and I found him, on my return to Turkey, some years after, elevated to the patriarchal throne. His suceptibility to the beauties of nature that smiled here in his prison, was not impaired by any dismal apprehensions. In his work, since published, he describes with enthusiasm the view presented from his island: "The prospect from hence," said he, " formed by the circle of lovely objects around, is inimitable on the earth; it stands like the varied representations of some grand amphitheatre, and the astonished and delighted eye, at sunset, sees the exceeding splendour of nature's scenery."

Fig.: The Princes Islands from the Monastery of the Trinity. Prinkipo is in the middle distance.

The view in our illustration is taken from the monastery of the Triades, or Trinity, in the island of Chalki. This edifice was erected by the patriarch Photios, who was named "the man of ten thousand books." He called it Zion, but its name was afterwards changed. His ten thousand books were deposited in a library: the greater part was destroyed by fire, which consumed nearly the whole edifice, and the rest by time and neglect, so that not one now remains. The present edifice, inhabited by the Caloyers, is but a wing ojf the original building. In the foreground, on a platform, is a kiosk, from whence is seen one of those lovely views which almost every eminence of the island presents. Attached to every monastery is such an edifice; it is kind of coffee-house, open to strangers, in which they repose, enjoying the beauty of the scenery, and are seen with pipes, coffee, and sweetmeats by the good monks. The view from this kiosk of the Triades, comprehending Europe and Asia, is particularly eulogized and described by the archbishop. The splendid city of Constantinople rising on its seven hills, with its gilded domes and glittering minarets ; the sweeping shores of Thrace; the Bithynian chain of mountains, in the midst of which Olympus raises his head, covered with eternal snows ; the whole circle of islands, floating below on the bosom of the placid sea—form an unrivalled panoramic picture.

Just below lies the varied face of the island, with its shrubs and trees; a range of gigantic cypresses leads, along the ridge of a sloping hill, to an edifice on the sea-shore; this was erected by an opulent Greek tchelebi, in the palmy days of their prosperity. He was suspected, apprehended, and executed, and his splendid mansion, containing all the requisites of modern Greek luxuries, was occupied by various Franks, who left the sultry heats of the capital for the refreshing breezes of the islands. Along the shore below run the streets of the capital of Chalki, with its fleet of small-craft lying in the harbour. Among the edifices are some which present an unusual sight in these islands: On a promontory, a minaret raises its taper head; and on the hill behind, is a Turkish kisla, or barracks. When the insurrection broke out, the immunities of the islands were withdrawn, and Moslem edifices and Moslem people are now seen mixed with the hitherto exclusive Greek population.

THE MONASTERY OF ST. GEORGE OF THE PRECIPICE.

There is no saint in the Oriental calendar held in more estimation, both by Moslems and Christians, than St. George of Cappadocia. The Greeks and Armenians dedicate many churches to him, and the legends they tell and believe of him correspond with those that are current in England of its patron saint. The Orientals do not reproach their favourite, as some incredulous historians do among us, with being the son of a fuller, becoming a parasite, a bacon-merchant, and a cheat, who was torn to pieces by his townsmen for his manifold crimes and vices, in the reign of Julian the Apostate. They represent him as a Christian hero, who suffered martyrdom for his inflexible adherence to Christianity in the persecution of Diocletian, but, before that, had distinguished himself by deeds of high heroic reputation. One of them seems a version of Perseus and Andromeda; and, as in many other instances, fables of pagan mythology are appropriated by Christian saints. After various achievements against Paynims and Saracens, he came to the land of Egypt in search of new adventures. He here found a winged dragon devastating the country with his pestiferous breath, and devouring those whom he had preserved. The wise men were called together, and a compact was made with the monster, that he should be content with devouring a virgin every day. They were all eaten, except the daughter of the soldan, and her weeping friends had just led her to the sacrifice, when St. George arrived. He attacked and slew the monster, and liberated the virgin. This legend, which corresponds with that of the old English ballad, is commemorated in this church of St. George, by a picture in the portico: the saint is depicted on horseback, piercing a winged dragon with a spear, exactly as he is represented on our coins and armorial blazonry; and so he is displayed in every one of the numerous churches dedicated to him in the East.

This fable, which is a popular legend both in the East and West, is, however, explained allegorically. The dragon is the devil, represented under that form in the Apocalypse; and subduing him, and trampling him under foot, by the saint, is emblematic of the faith and fortitude of a Christian. The Greeks call St. George the Megalomartyr and his festival is a holiday "of obligation." Constantine the Great built a church, which stood over his tomb in Palestine, and erected the first to his memory in the metropolis, where there were afterwards five more dedicated to him. Justinian, in the sixth century, introduced him into the Armenian calendar, and raised a temple to him. At the entrance into the Hellespont is a large and celebrated convent of his order, which gives his name to the strait; and the pagan appellation of Hellespont merged into the Christian one of "the Arm of St. George." He was the great patron of Christian knights, and none went to battle without first offering to him their vows.

When Richard Coeur de Lion laid siege to Acre, the saint appeared to him in a vision, and the Crusaders attributed their victories to his interference and aid. The great national council, held at Oxford in 1222, recognized him, and commanded his feast to be kept as a holiday; and in 1330, Edward III instituted an order of knighthood to his name in England, one of the oldest in Europe, and so he has become the patron-saint of England. His festival is celebrated on the 23d of April, in the Greek church; and the English ambassador at Constantinople, as if to identify our patron-saint with that of the Greeks, gives a splendid entertainment on the same day at the British palace, where St. George is held "as the patron of arms, chivalry, and the garter."

But our saint has immunities and privileges which do not appear to be allowed to any other in the Greek calendar. At the early period of the reformation in the Oriental church, statues were everywhere torn down by the Iconoclasts, and excluded from their worship as idolatrous, though pictures were allowed to remain; adhering literally to the commandment of making " no graven images," but, by a singular anomaly of Greek refinement, venting their religious horror on wood and stone, and bowing down without scruple to paint and canvass. This distinction continues in all its strictness to the present day : the churches are profusely daubed with gaudy pictures of saints, to which profound adoration is paid, and the most extraordinary miracles are attributed ; while no statue, or sculptured or graven representation, of the same persons, are tolerated : but to our saint alone an indulgence is extended. His image in some churches is formed on graven silver plates attached to a wooden block, which they affirm had miraculously escaped from the destruction of the Iconoclasts, and has peculiar faculties conferred upon it, corresponding with the pugnacious propensities of the character whose person it represents ; and to its wonder-working powers many miracles are attributed.

Fig. : Monastery of St. George of the Precipice. Princes Islands. [In fact, St. George of Chalki]

In the monastery of St. George, in one of the islands of the Archipelago, is a statue of this kind, which is highly serviceable to the Caloyers. If any one is indebted to the convent, and does not pay his dues — if a penitent omits to perform the penance, or violates the strict abstinence imposed upon him during the many seasons of fasting — above all, if he neglects to perform any vow made to the saint — the image immediately finds him out. It is placed on the shoulders of a blind monk, who trusts implicitly to its guidance, and walks fearlessly on without making a false step. It is in vain that the sinning defaulter tries to hide himself. The image follows him through all his windings with infallible sagacity, and, when at length he is overtaken, springs from the shoulders of his bearer to the neck of the culprit, and flogs him with unmerciful severity till he makes restitution and atonement for all his delinquencies. A French writer, who was a firm believer in the miracles wrought by the images of saints in the Latin church, in recording these absurdities of St. George, adds with great naivete : Les Grecs sont les plus grands imposteurs du mond.

In the church of the convent is a picture highly prized as a chef d’oeuvre of Grecian art; it represents the last day, a subject which the Greek Caloyers are fond of impressing on their people. In some, the punishments of a future state, as painted on the walls, are hardly fit to be looked at. Devils riding ploughshares, and driving them through naked bodies of men, and serpents twining round the limbs of offending women. This picture, however, is less exceptionable; it depicts the Deity on the summit, dressed in sumptuous robes, and crowned like a king, having an expanded book before him, in which the fate of every mortal is recorded: below, on one side is a garden, having various departments like the pews of a church, in each of which is enclosed some celebrated individual. In one, Abraham with Lazarus in his bosom, — in another, the penitent thief with his cross on his shoulder. Immediately below, are the extended jaws of a vast monster, into which demons are casting the souls of the condemned, among whom are all the apostates and persecutors of Christianity — Judas, Julian, and Diocletian; with sundry Turks. Among the condemned, one is surprised to see a Greek with his calpac; he had been a dragoman of the Porte, who had offended the artist, and he took this not unprecedented mode of avenging himself on his adversary.