Colville Frankland, Charles (1827)

18 mai 1827

Fils d’un pasteur anglais, Charles Colville Frankland naît à Bath en 1797. En 1813 il entre au Royal Naval College, puis il fait l’ensemble de sa carrière comme officier de la Marine britanique, notamment en Amérique. De 1827 à 1828, il effectue un séjour en Orient. Les impressions de son voyage sont contenues dans un Journal qui reflète la position très critique de son auteur envers les autorités et l’administration ottomanes. Sans prétention scientifique et avec plusieurs approximations, ce texte donne un grand nombre de descriptions des lieux que Colville a visités et des personnes qu’il a rencontrées.

Dans la partie de son récit concernant les Îles des Princes, il dit avoir visité les monastères de la Panaghia et de la Sainte-Trinité à Chalki, ainsi qu’un sanctuaire dédié à la Vierge, où il vit des malades venus chercher la guérison. Il s’agit sans doute du monastère de Saint-Georges, lieu réputé pour ses miracles.

Charles Colville Frankland meurt en 1876.

Texte français : Jean-Pierre Grélois

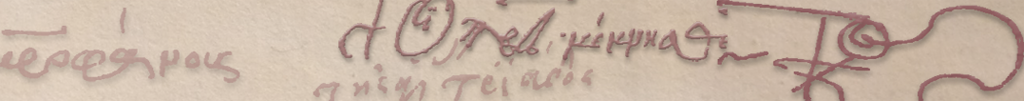

13 mai [1827] — J’eus l’honneur d’accompagner l’ambassadeur, son épouse et sa suite dans le splendide canot de Son Excellence, monté par six kalyoncı (chacun actionnant deux avirons) et barré par un vénérable vieux re’is, vers les îles de la Propontide. On en compte quatre, à savoir Antigone, Protè, Chalki et Prinkipo. Nous débarquâmes d’abord à Chalki (« cuivre », qui tire son nom de ce métal qui y abonde) et nous allâmes au hasard par des collines couvertes d’arbousiers, de myrtes, de cistes à gomme, de sauge sauvage et d’une variété de fleurs sylvestres, jusqu’à un monastère de popes grecs [= Panaghia]. Là, au-dessus du seuil de la porte, se trouve la tombe de Sir Edward Barton. J’ai copié l’inscription que j’insère ci-après:

Ces monastères grecs ne présentent rien de remarquable, sauf que je peux excepter la présence d’un grand nombre de femmes et d’enfants. Les popes ont la permission, quand ils sont dans l’ordre des diacres, de se marier et ils cohabitent avec leurs épouses jusqu’à leur élévation à la dignité épiscopale laquelle, du fait qu’elle n’incombe qu’à une part relativement limitée, ne gêne pas souvent leurs affaires domestiques. Ils semblaient être pour la plupart des hommes très ignorants et rustres, mais ils étaient extrêmement humbles, polis et obligeants. Il y a dans cette île un autre de ces couvents sur le sommet d’une haute colline [= Sainte Trinité], où nous allâmes de même pour y profiter de la belle vue sur la mer de Marmara et au loin sur les minarets et les coupoles d’Istanbul. Là je fis une esquisse. Il y avait dans le monastère une curieuse peinture du Jugement Dernier, avec toutes ses horreurs et bizarreries concomitantes, égal en tous points à l’œuvre célèbre traitée sur ce sujet par Michel-Ange à la Chapelle Sixtine.

Il y a une jolie localité du côté sud de l’île, avec quelques belles maisons où de nombreuses familles séjournent pendant les chaleurs de l’été. L’internonce autrichien y a une villa. Nous rendîmes visites à la famille du premier drogman de l’ambassade britannique et nous promenâmes sur les quais de l’endroit, avec les belles de Chalki. Nous allâmes ensuite en canot par grosse mer (car la brise de mer s’était élevée) vers Prinkipo ; et là, après avoir erré au hasard quelque temps, nous dînâmes sous un arbre immense au centre d’un village grec.

Nous fûmes distraits pendant notre repas par un groupe de musiciens turcs et une douzaine de Grecs qui dansaient la romaïque au son barbare de l’orchestre ambulant […] Après le dîner, nous nous procurâmes des ânes et presque toute la compagnie chevaucha par les hauteurs pour jouir des vues et visiter le fameux sanctuaire de la Panaghia [= Saint Georges], contenu dans un couvent ancien près du sommet de la colline. Dans la chapelle nous trouvâmes deux ou trois malades gisant sur des matelas à même le sol : on nous dit qu’ils étaient venus là afin que l’Église priât pour eux ; mais, à en juger de leur apparence, il ne semblerait pas que ces prières aient été bien efficaces. Il s’agit d’une pratique commune dans l’Église grecque, et elle est de grande antiquité.

Nous vîmes quelques pauvres fous furieux dans la cour du couvent, enchaînés comme des malfaiteurs ; et une malheureuse créature qui semblait tout bonnement idiote était soumise à la même espèce de contrainte. Ces misérables objets avaient été aussi amenés là dans la même pieuse intention.

Les Grecs croient en la vieille superstition de la possession par les diables ; et je comprends plutôt que la folie furieuse et la possession semblent être à leurs yeux une seule et même chose. De là la coutume d’amener ici les fous furieux dans le sanctuaire de la Panaghia pour qu’on les exorcise et prie sur eux. Nous ne pouvons disputer de leur piété, bien que nous pouvions prendre leur ignorance en pitié. L’île de Prinkipo possède sur sa côte sud de nombreux restes d’antiquité, des bains, colonnes, fragments d’autel etc. etc. On y trouve fréquemment des monnaies des empereurs romains et grecs.

Nous revînmes aux bateaux au coucher du soleil et nous eûmes un retour long et fatiguant à Tophane où nous débarquâmes à près de minuit. Nous fûmes poursuivis en montant par les rues escarpées et inégales par toute la bande des chiens de Tophane, jappant à nos talons sur presque tout le chemin jusqu’à Galatasaray. Nous étions tous fatigués et affamés et je fus bien content d’accepter une invitation à souper au palais.

May 13. — I had the honour of accompanying the Ambassador, his lady, and suite, in his Excellency’s splendid barge, manned by seven galiongees, (each pulling two oars,) and steered by a venerable old Reis, to the Islands of the Propontis. They are four in number, viz. Antigone, Protæ, Chalki, and Principo. We landed first upon Chalki, (copper, so called from that metal abounding there), and wandered over hills covered with arbutus, myrtle, gum-cistus, wild-sage, thyme, and a variety of sylvan flowers, to a monastery of Greek Papas. Here, over the sill of the door, is the tombstone of Sir Edward Barton. I have copied the inscription, which I insert below:

These Greek monasteries present nothing remarkable, unless I may except the presence of many women and children. The papas are allowed, while in deacon’s orders, to marry, and they cohabit with their wives until their elevation to the episcopal dignity, which, as it falls to the share of comparatively few, does not often interfere with their domestic arrangements. They seemed to be mostly very ignorant and clownish men ; but they were extremely humble, civil, and obliging. There is another of those convents on the top of a high hill in this island, whither we likewise went to enjoy from thence the fine view of the Sea of Marmora, and the distant minarets and domes of Stambool. Here I made a sketch. In the monastery was a curious picture of the Last Jugement, with all its concomitant horrors and whimsicalities, equal to any thing of the sort in the celebrated performance upon that subject by Michel Angelo, in the Sistine Chapel.

There is a pretty town on the south side of the island, with some good houses in it, whither many families resort in the heats of summer. The Austrian Internuncio has a villa here. We called upon the family of the first dragoman to the British Embassy, and walked about upon the quays of the place, with the belles of Chalki. We afterwards went in the barge through a heavy sea (for the sea-breeze hat set in,) to the island of Principo ; and here, after wandering about some time, we dined under an immense tree in the centre of a Greek village.

We were entertained during our repast by a group of Turkish musicians, and by about a dozen Greeks, who danced the Romäika to the barbarous sounds of the itinerant band. […] After dinner, we procured asses, and almost all the party rode up over the heights to obtain views, and to visit the famous shrine of the Panagia, contained in an old convent near the summit of the mountain. In the chapel we found two or three sick people lying upon mattresses on the floor : they told us, they had come hither to be prayed for by the Church ; but, judging from their appearance, it would not seem that these prayers had been very efficacious. This is a common practice in the Greek Church, and is of great antiquity.

We saw some poor maniacs in the court-yard of the convent, chained like malefactors ; and one wretched creature, who seemed to be merely idiotical, was under the same species of restraint. These miserable objects were likewise brought hither for the same pious purpose.

The Greeks believe in the old superstition of the possession of devils ; and I rather apprehend that mania and possession seem to be in their eyes one and the same thing. Hence the custom of bringing maniacs hither to the shrine of the Panagia, to be exorcised and prayed over. We cannot quarel with their piety, although we may pity their ignorance. The island of Principo, on its southern shore, possesses many remains of antiquity, some baths, columns, fragments of altars, &c. &c. Coins of the Roman and Greek emperors are frequeltly found here.

We returned at sunset to the boats, and had a long and weary pull back to Tophana, where we landed at nearly midnight, and were pursued up the steep and uneven streets by the whole pack of Tophana hounds, yelping at our heels nearly all the way to the Galata Seraï. We were all weary and hungry, and I was glad to accept an invitation to sup at the palace.